Merry Christmas Baby You Sure Have Treated Me Well

1848 delineation of Father Christmas crowned with a holly wreath, holding a staff and a wassail basin and conveying the Yule log

Male parent Christmas is the traditional English language proper name for the personification of Christmas. Although now known as a Christmas souvenir-bringer, and typically considered to exist synonymous with Santa Claus, he was originally part of a much older and unrelated English folkloric tradition. The recognisably modern figure of the English language Begetter Christmas developed in the late Victorian catamenia, but Christmas had been personified for centuries before so.[1]

English personifications of Christmas were kickoff recorded in the 15th century, with Father Christmas himself starting time actualization in the mid 17th century in the backwash of the English Civil War. The Puritan-controlled English language government had legislated to abolish Christmas, because it papist, and had outlawed its traditional customs. Royalist political pamphleteers, linking the one-time traditions with their cause, adopted Old Father Christmas as the symbol of 'the expert old days' of feasting and adept cheer. Following the Restoration in 1660, Father Christmas's profile declined. His grapheme was maintained during the tardily 18th and into the 19th century by the Christmas folk plays later known as mummers plays.

Until Victorian times, Father Christmas was concerned with adult feasting and merry-making. He had no particular connection with children, nor with the giving of presents, nocturnal visits, stockings, chimneys or reindeer. But as after Victorian Christmases developed into child-centric family unit festivals, Father Christmas became a bringer of gifts.

The pop American myth of Santa Claus arrived in England in the 1850s and Male parent Christmas started to take on Santa'due south attributes. Past the 1880s the new customs had get established, with the nocturnal visitor sometimes being known equally Santa Claus and sometimes every bit Male parent Christmas. He was often illustrated wearing a long red hooded gown trimmed with white fur.

Virtually balance distinctions betwixt Father Christmas and Santa Claus largely faded away in the early years of the 20th century, and modern dictionaries consider the terms Father Christmas and Santa Claus to be synonymous.

Early midwinter celebrations [edit]

The custom of merrymaking and feasting at Christmastide first appears in the historical record during the High Middle Ages (c 1100–1300).[2] This almost certainly represented a continuation of pre-Christian midwinter celebrations in Britain of which—as the historian Ronald Hutton has pointed out—"we have no details at all".[2] Personifications came later, and when they did they reflected the existing custom.

15th century—the first English personifications of Christmas [edit]

The first known English personification of Christmas was associated with merry-making, singing and drinking. A carol attributed to Richard Smart, Rector of Plymtree in Devon from 1435 to 1477, has 'Sir Christemas' announcing the news of Christ'southward birth and encouraging his listeners to beverage: "Buvez bien par toute la compagnie, / Make good cheer and be right merry, / And sing with usa now joyfully: Nowell, nowell."[iii]

Many late medieval Christmas customs incorporated both sacred and secular themes.[4] In Norwich in Jan 1443, at a traditional battle between the flesh and the spirit (represented past Christmas and Lent), John Gladman, crowned and bearded equally 'Rex of Christmas', rode backside a pageant of the months "disguysed as the seson requird" on a horse decorated with tinfoil.[4]

16th century—feasting, entertainment and music [edit]

In virtually of England the primitive give-and-take 'Yule' had been replaced by 'Christmas' by the 11th century, merely in some places 'Yule' survived as the normal dialect term.[five] The Metropolis of York maintained an almanac St Thomas's Mean solar day celebration of The Riding of Yule and his Wife which involved a figure representing Yule who carried bread and a leg of lamb. In 1572 the riding was suppressed on the orders of the Archbishop, who complained of the "undecent and uncomely disguising" which drew multitudes of people from divine service.[6]

Such personifications, illustrating the medieval fondness for pageantry and symbolism,[v] extended throughout the Tudor and Stuart periods with Lord of Misrule characters, sometimes chosen 'Captain Christmas',[1] 'Prince Christmas'[one] or 'The Christmas Lord', presiding over feasting and entertainment in grand houses, university colleges and Inns of Court.[3]

In his emblematic play Summer'due south Concluding Will and Attestation,[seven] written in about 1592, Thomas Nashe introduced for comic effect a miserly Christmas character who refuses to keep the feast. He is reminded past Summer of the traditional role that he ought to be playing: "Christmas, how chance yard com'st not every bit the rest, / Accompanied with some music, or some song? / A merry ballad would have graced thee well; / Thy ancestors have used information technology heretofore."[eight]

17th century—faith and politics [edit]

Puritan criticisms [edit]

Early 17th century writers used the techniques of personification and allegory as a means of defending Christmas from attacks by radical Protestants.[9]

Responding to a perceived pass up in the levels of Christmas hospitality provided by the gentry,[x] Ben Jonson in Christmas, His Masque (1616) dressed his Old Christmas in out-of-date fashions:[xi] "attir'd in round Hose, long Stockings, a close Doublet, a loftier crownd Lid with a Broach, a long thin beard, a Truncheon, piddling Ruffes, white shoes, his Scarffes, and Garters tyed crosse". Surrounded past guards, Christmas asserts his rightful place in the Protestant Church building and protests against attempts to exclude him:[12] "Why Gentlemen, doe y'all know what yous doe? ha! would y'all ha'kept me out? Christmas, old Christmas? Christmas of London, and Captaine Christmas? ... they would non permit me in: I must come another time! a good jeast, as if I could come more then once a yeare; why, I am no dangerous person, and so I told my friends, o'the Guard. I am onetime Gregorie Christmas still, and though I come out of Popes-head-alley as skillful a Protestant, every bit any i'my Parish."[13]

The stage directions to The Springs Glorie, a 1638 court masque by Thomas Nabbes, country, "Christmas is personated by an old reverend Gentleman in a furr'd gown and cappe &c."[nine] Shrovetide and Christmas dispute precedence, and Shrovetide issues a challenge: "I say Christmas you are past date, you are out of the Almanack. Resigne, resigne." To which Christmas responds: "Resigne to thee! I that am the King of skillful cheere and feasting, though I come but once a yeare to raigne over bak't, boyled, roast and plum-porridge, will have being in despight of thy lard-ship."[14]

This sort of character was to characteristic repeatedly over the next 250 years in pictures, phase plays and folk dramas. Initially known as 'Sir Christmas' or 'Lord Christmas', he later became increasingly referred to as 'Father Christmas'.[nine]

Puritan revolution—enter 'Father Christmas' [edit]

The ascension of puritanism led to accusations of popery in connection with pre-reformation Christmas traditions.[3] When the Puritans took control of government in the mid-1640s they made concerted efforts to abolish Christmas and to outlaw its traditional community.[15] For fifteen years from around 1644, earlier and during the Interregnum of 1649-1660, the commemoration of Christmas in England was forbidden.[15] The suppression was given greater legal weight from June 1647 when parliament passed an Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals [xvi] which formally abolished Christmas in its entirety, forth with the other traditional church festivals of Easter and Whitsun.[10]

It was in this context that Royalist pamphleteers linked the quondam traditions of Christmas with the cause of King and Church, while radical puritans argued for the suppression of Christmas both in its religious and its secular aspects.[17] In the hands of Royalist pamphlet writers, Onetime Father Christmas served equally the symbol and spokesman of 'the good former days' of feasting and good cheer,[1] and information technology became popular for Christmastide's defenders to present him as lamenting past times.[18]

The Arraignment, Conviction and Imprisoning of Christmas (January 1646) describes a give-and-take between a town crier and a Royalist gentlewoman enquiring later on Old Begetter Christmas who 'is gone from hence'.[xv] Its anonymous writer, a parliamentarian, presents Father Christmas in a negative light, concentrating on his allegedly popish attributes: "For age, this hoarie headed man was of bang-up yeares, and as white as snow; he entred the Romish Kallender fourth dimension out of mind; [he] is one-time ...; he was full and fat equally whatsoever dumb Docter of them all. He looked under the consecrated Laune sleeves as large as Bul-beefe ... but, since the catholike liquor is taken from him, he is much wasted, and then that he hath looked very thin and ill of late ... But yet some other markes that you may know him by, is that the wanton Women dote later him; he helped them to so many new Gownes, Hatts, and Hankerches, and other fine knacks, of which he hath a pack on his back, in which is good store of all sorts, besides the fine knacks that he got out of their husbands' pockets for household provisions for him. He got Prentises, Servants, and Schollars many play dayes, and therefore was well dearest by them also, and made all merry with Bagpipes, Fiddles, and other musicks, Giggs, Dances, and Mummings."[19]

Father Christmas depicted in The Vindication of Christmas, 1652

The character of 'Christmas' (also chosen 'father Christmas') speaks in a pamphlet of 1652, immediately after the English Ceremonious War, published anonymously past the satirical Royalist poet John Taylor: The Vindication of Christmas or, His Twelve Yeares' Observations upon the Times. A frontispiece illustrates an old, bearded Christmas in a brimmed hat, a long open robe and undersleeves. Christmas laments the pitiful quandary he has fallen into since he came into "this headlesse countrey". "I was in good hope that so long a misery would have fabricated them glad to bid a merry Christmas welcome. But welcome or not welcome, I am come...." He concludes with a poetry: "Lets dance and sing, and make good chear, / For Christmas comes but one time a year."[twenty]

Begetter Christmas, equally illustrated in Josiah King'south ii pamphlets of 1658 and 1678

In 1658 Josiah King published The Test and Tryall of Old Father Christmas (the earliest commendation for the specific term 'Begetter Christmas' recognised by the Oxford English Dictionary).[21] King portrays Male parent Christmas equally a white-haired former man who is on trial for his life based on evidence laid against him by the Commonwealth. Begetter Christmas's counsel mounts the defense force: "Me thinks my Lord, the very Clouds blush, to come across this sometime Gentleman thus egregiously driveling. if at any time whatever have abused themselves by immoderate eating, and drinking or otherwise spoil the creatures, it is none of this quondam mans fault; neither ought he to suffer for it; for instance the Sun and the Moon are by the heathens worship'd are they therefore bad because idolized? so if any abuse this erstwhile man, they are bad for abusing him, not he bad, for beingness abused." The jury acquits.[22] [23]

Restoration [edit]

Following the Restoration in 1660, about traditional Christmas celebrations were revived, although as these were no longer contentious the historic documentary sources become fewer.[24]

In 1678 Josiah King reprinted his 1658 pamphlet with additional textile. In this version, the restored Begetter Christmas is looking meliorate: "[he] look't and so smug and pleasant, his ruddy cheeks appeared through his thin milk white locks, like [b]lushing Roses vail'd with snow white Tiffany ... the true Emblem of Joy and Innocence."[25]

Old Christmass Returnd, a ballad nerveless by Samuel Pepys, celebrated the revival of festivities in the latter part of the century: "Old Christmass is come up for to keep open house / He scorns to be guilty of starving a mouse, / So come up boyes and welcome, for dyet the master / Plumb pudding, Goose, Capon, minc't pies & Roast beef".[26]

18th century—a low profile [edit]

As interest in Christmas customs waned, Begetter Christmas's contour declined.[1] He still connected to be regarded as Christmas'southward presiding spirit, although his occasional earlier associations with the Lord of Misrule died out with the disappearance of the Lord of Misrule himself.[1] The historian Ronald Hutton notes, "after a gustatory modality of genuine misrule during the Interregnum nobody in the ruling elite seems to have had any stomach for simulating information technology."[27] Hutton also plant "patterns of entertainment at belatedly Stuart Christmases are remarkably timeless [and] nothing very much seems to have altered during the next century either."[27] The diaries of 18th and early 19th century clergy take piffling note of any Christmas traditions.[24]

In The Country Squire, a play of 1732, Quondam Christmas is depicted as someone who is rarely-constitute: a generous squire. The character Scabbard remarks, "Men are grown then ... stingy, now-a-days, that in that location is scarce Ane, in x Parishes, makes any House-keeping. ... Squire Christmas ... keeps a good House, or else I do non know of One too." When invited to spend Christmas with the squire, he comments "I will ... else I shall forget Christmas, for aught I run across."[28] Like opinions were expressed in Round Nearly Our Coal Fire ... with some curious Memories of Former Father Christmas; Shewing what Hospitality was in former Times, and how little there remains of it at present (1734, reprinted with Begetter Christmas subtitle 1796).[29]

David Garrick'due south pop 1774 Drury Lane product of A Christmas Tale included a personified Christmas character who announced "Behold a personage well known to fame; / Once lov'd and laurels'd – Christmas is my proper name! /.../ I, English hearts rejoic'd in days of yore; / for new strange modes, imported by the score, / Yous will not sure plough Christmas out of door!"[xxx] [31]

Early records of folk plays [edit]

By the tardily 18th century Father Christmas had become a stock grapheme in the Christmas folk plays later known as mummers plays. During the post-obit century they became probably the most widespread of all agenda customs.[32] Hundreds of villages had their own mummers who performed traditional plays around the neighbourhood, especially at the big houses.[33] Father Christmas appears as a graphic symbol in plays of the Southern England blazon,[34] [35] existence mostly confined to plays from the south and due west of England and Wales.[36] His ritual opening spoken communication is characterised by variants of a couplet closely reminiscent of John Taylor'due south "But welcome or not welcome, I am come..." from 1652.

The oldest extant oral communication[36] [37] is from Truro, Cornwall in the belatedly 1780s:

-

hare comes i ould father Christmas welcom or welcom non

i hope ould father Christmas volition never be forgot

ould father Christmas a pair only woance a yare

he lucks like an ould man of 4 score yare[38]Here comes I, former Male parent Christmas, welcome or welcome not,

I hope quondam Begetter Christmas will never be forgot.

Old Father Christmas appear[s] but once a year,

He looks similar an sometime man of 80 year [80].

19th century—revival [edit]

During the Victorian period Christmas customs enjoyed a significant revival, including the figure of Begetter Christmas himself every bit the emblem of 'good cheer'. His physical appearance at this time became more variable, and he was by no means always portrayed as the old and disguised effigy imagined by 17th century writers.[3]

'Merry England' view of Christmas [edit]

In his 1808 poem Marmion, Walter Scott wrote:

- "England was merry England, when / Old Christmas brought his sports again.

- 'Twas Christmas broach'd the mightiest ale; / 'Twas Christmas told the merriest tale;

- A Christmas gambol oft could cheer / The poor man's heart through half the twelvemonth."[39]

Scott's phrase Merry England has been adopted by historians to describe the romantic notion that there was a gilded historic period of the English past, allegedly since lost, that was characterised by universal hospitality and charity. The notion had a profound influence on the manner that popular customs were seen, and nearly of the 19th century writers who bemoaned the state of contemporary Christmases were, at least to some extent, yearning for the mythical Merry England version.[40]

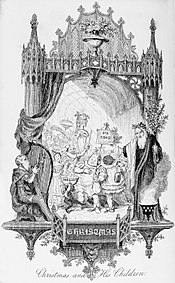

Thomas Hervey's The Book of Christmas (1836), illustrated past Robert Seymour, exemplifies this view.[41] In Hervey'southward personification of the lost charitable festival, "Old Begetter Christmas, at the head of his numerous and uproarious family, might ride his goat through the streets of the city and the lanes of the village, but he dismounted to sit for some few moments by each man'south hearth; while some one or another of his merry sons would break away, to visit the remote farm-houses or evidence their laughing faces at many a poor man'southward door." Seymour'south analogy shows Quondam Christmas dressed in a fur gown, crowned with a holly wreath, and riding a yule goat.[42]

Christmas with his children 1836

In an extended allegory, Hervey imagines his gimmicky Onetime Male parent Christmas as a white-bearded magician dressed in a long robe and crowned with holly. His children are identified equally Roast Beefiness (Sir Loin) and his faithful squire or canteen-holder Plum Pudding; the slender effigy of Wassail with her fount of perpetual youth; a 'tricksy spirit' who bears the basin and is on the best of terms with the Turkey; Mumming; Misrule, with a plume in his cap; the Lord of Twelfth Night under a state-canopy of cake and wearing his ancient crown; Saint Distaff looking similar an old maid ("she used to be a sad romp; but her merriest days we fear are over"); Carol singing; the Waits; and the twin-faced Janus.[43]

Hervey ends by lamenting the lost "uproarious merriment" of Christmas, and calls on his readers "who know anything of the 'sometime, old, very old, gray-disguised admirer' or his family to assist us in our search after them; and with their skilful help nosotros volition attempt to restore them to some portion of their ancient honors in England".[44]

Begetter Christmas or Quondam Christmas, represented every bit a jolly-faced bearded homo often surrounded by plentiful nutrient and drink, started to announced regularly in illustrated magazines of the 1840s.[i] He was dressed in a diverseness of costumes and usually had holly on his head,[1] as in these illustrations from the Illustrated London News:

- Illustrated London News, 1840s

-

Old Christmas 1842

-

Old Christmas / Father Christmas 1843

-

Old Christmas 1847

Charles Dickens's 1843 novel A Christmas Carol was highly influential, and has been credited both with reviving interest in Christmas in England and with shaping the themes attached to information technology.[45] A famous image from the novel is John Leech'south analogy of the 'Ghost of Christmas Present'.[46] Although non explicitly named Male parent Christmas, the graphic symbol wears a holly wreath, is shown sitting among nutrient, drink and wassail bowl, and is dressed in the traditional loose furred gown—but in green rather than the red that later become ubiquitous.[three]

Later 19th century mumming [edit]

Former Male parent Christmas continued to make his almanac appearance in Christmas folk plays throughout the 19th century, his appearance varying considerably according to local custom. Sometimes, as in Hervey'southward book of 1836,[47] he was portrayed (below left) every bit a hunchback.[48] [49]

One unusual portrayal (below eye) was described several times by William Sandys between 1830 and 1852, all in essentially the aforementioned terms:[32] "Begetter Christmas is represented as a grotesque erstwhile man, with a large mask and comic wig, and a huge club in his paw."[l] This representation is considered by the folklore scholar Peter Millington to exist the consequence of the southern Begetter Christmas replacing the northern Beelzebub graphic symbol in a hybrid play.[32] [51] A spectator to a Worcestershire version of the St George play in 1856 noted, "Beelzebub was identical with Old Father Christmas."[52]

A mummers play mentioned in The Book of Days (1864) opened with "Sometime Father Christmas, bearing, as emblematic devices, the holly bough, wassail-bowl, &c".[53] A respective analogy (beneath right) shows the character wearing not simply a holly wreath but besides a gown with a hood.

- Old Father Christmas in folk plays

-

A hunchback Old Begetter Christmas in an 1836 play with long robe, holly wreath and staff.

-

An 1852 play. The Former Father Christmas character is on the far left.

-

A party of mummers 1864

In a Hampshire folk play of 1860 Male parent Christmas is portrayed as a disabled soldier: "[he] wore breeches and stockings, carried a begging-box, and conveyed himself upon two sticks; his arms were striped with chevrons like a noncommissioned officer."[54]

In the latter role of the 19th century and the early years of the next the folk play tradition in England rapidly faded,[55] and the plays almost died out subsequently the First Earth State of war[56] taking their ability to influence the grapheme of Father Christmas with them.

Male parent Christmas every bit souvenir-giver [edit]

In pre-Victorian personifications, Male parent Christmas had been concerned essentially with adult feasting and games. He had no detail connection with children, nor with the giving of presents.[1] [nine] But as Victorian Christmases developed into family festivals centred mainly on children,[57] Male parent Christmas started to be associated with the giving of gifts.

The Cornish Quaker diarist Barclay Fob relates a family party given on 26 December 1842 that featured "the venerable effigies of Father Christmas with ruby coat & artsy hat, stuck all over with presents for the guests, by his side the old year, a most dismal & haggard quondam beldame in a nighttime cap and glasses, then 1843 [the new year], a promising babe comatose in a cradle".[58]

In Britain, the kickoff show of a child writing letters to Father Christmas requesting gift has been found in 1895.[59]

Santa Claus crosses the Atlantic [edit]

The figure of Santa Claus had originated in the US, cartoon at to the lowest degree partly upon Dutch St Nicolas traditions.[9] A New York publication of 1821, A New-Year's Present, contained an illustrated poem Erstwhile Santeclaus with Much Please in which a Santa figure on a reindeer sleigh brings presents for skillful children and a "long, black birchen rod" for apply on the bad ones.[60] In 1823 came the famous poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, usually attributed to the New York author Clement Clarke Moore, which developed the graphic symbol farther. Moore'due south poem became immensely popular[1] and Santa Claus customs, initially localized in the Dutch American areas, were becoming general in the United states of america by the middle of the century.[48]

Santa Claus, equally presented in Howitt's Journal of Literature and Pop Progress, London 1848

The January 1848 edition of Howitt's Journal of Literature and Popular Progress, published in London, carried an illustrated article entitled "New year's Eve in Different Nations". This noted that one of the chief features of the American New Twelvemonth's Eve was a custom carried over from the Dutch, namely the arrival of Santa Claus with gifts for the children. Santa Claus is "no other than the Pelz Nickel of Germany ... the adept Saint Nicholas of Russia ... He arrives in Germany nigh a fortnight earlier Christmas, but equally may be supposed from all the visits he has to pay in that location, and the length of his voyage, he does not arrive in America, until this eve."[61]

In 1851 advertisements began appearing in Liverpool newspapers for a new transatlantic rider service to and from New York aboard the Hawkeye Line'south send Santa Claus,[62] and returning visitors and emigrants to the British Isles on this and other vessels volition have been familiar with the American figure.[48] There were some early adoptions in Britain. A Scottish reference has Santa Claus leaving presents on New year's day's Eve 1852, with children "hanging their stockings up on each side of the fire-place, in their sleeping apartments, at night, and waiting patiently till morning, to see what Santa Claus puts into them during their slumbers".[63] In Ireland in 1853, on the other hand, presents were existence left on Christmas Eve co-ordinate to a character in a newspaper short story who says "... tomorrow will be Christmas. What volition Santa Claus bring us?"[64] A verse form published in Belfast in 1858 includes the lines "The children sleep; they dream of him, the fairy, / Kind Santa Claus, who with a right practiced volition / Comes down the chimney with a stride airy ..."[65]

A Visit from St. Nicholas was published in England in December 1853 in Notes and Queries. An explanatory annotation states that the St Nicholas effigy is known as Santa Claus in New York State and equally Krishkinkle in Pennsylvania.[66]

1854 marked the first English publication of Carl Krinkin; or, The Christmas Stocking by the pop American writer Susan Warner.[1] The novel was published three times in London in 1854–5, and there were several later editions.[67] Characters in the book include both Santa Claus (complete with sleigh, stocking and chimney),[67] leaving presents on Christmas Eve and—separately—Old Father Christmas. The Stocking of the championship tells of how in England, "a great many years ago", it saw Male parent Christmas enter with his traditional refrain "Oh! here come I, old father Christmas, welcome or not ..." He wore a crown of yew and ivy, and he carried a long staff topped with holly-berries. His dress "was a long brownish robe which cruel down about his feet, and on it were sewed piddling spots of white cloth to represent snow".[68]

Merger with Santa Claus [edit]

Every bit the U.s.-inspired community became popular in England, Begetter Christmas started to take on Santa'southward attributes.[1] His costume became more standardised, and although depictions often still showed him conveying holly, the holly crown became rarer and was frequently replaced with a hood.[i] [9] It nonetheless remained common, though, for Male parent Christmas and Santa Claus to be distinguished, and equally late equally the 1890s there were still examples of the old-style Male parent Christmas appearing without whatever of the new American features.[69]

Appearances in public [edit]

The blurring of public roles occurred quite speedily. In an 1854 newspaper clarification of the public Boxing Day festivities in Luton, Bedfordshire, a gift-giving Father Christmas/Santa Claus figure was already being described every bit 'familiar': "On the correct-hand side was Father Christmas's bower, formed of evergreens, and in forepart was the proverbial Yule log, glistening in the snowfall ... He wore a great furry white coat and cap, and a long white beard and pilus spoke to his hoar antiquity. Behind his bower he had a big pick of fancy articles which formed the gifts he distributed to holders of prize tickets from fourth dimension to time during the day ... Begetter Christmas bore in his hand a pocket-sized Christmas tree laden with bright petty gifts and bon-bons, and altogether he looked like the familiar Santa Claus or Begetter Christmas of the movie volume."[seventy] Discussing the shops of Regent Street in London, another writer noted in December of that year, "yous may fancy yourself in the habitation of Begetter Christmas or St. Nicholas himself."[71]

During the 1860s and 70s Father Christmas became a popular subject field on Christmas cards, where he was shown in many different costumes.[49] Sometimes he gave presents and sometimes received them.[49]

Erstwhile Father Christmas, or The Cave of Mystery 1866

An illustrated article of 1866 explained the concept of The Cave of Mystery. In an imagined children's political party this took the form of a recess in the library which evoked "dim visions of the cave of Aladdin" and was "well filled ... with all that delights the eye, pleases the ear, or tickles the fancy of children". The young guests "tremblingly wait the decision of the improvised Father Christmas, with his flowing grayness beard, long robe, and slender staff".[72]

Father Christmas 1879, with holly crown and wassail bowl, the bowl now beingness used for the delivery of children'southward presents

From the 1870s onwards, Christmas shopping had begun to evolve equally a separate seasonal activity, and by the late 19th century it had become an of import part of the English language Christmas.[73] The purchasing of toys, especially from the new department stores, became strongly associated with the season.[74] The beginning retail Christmas Grotto was gear up in JR Robert'due south shop in Stratford, London in December 1888,[73] and shopping arenas for children—ofttimes called 'Christmas Bazaars'—spread quickly during the 1890s and 1900s, helping to assimilate Male parent Christmas/Santa Claus into order.[73]

Sometimes the ii characters connected to be presented as separate, equally in a procession at the Olympia Exhibition of 1888 in which both Father Christmas and Santa Claus took part, with Little Ruddy Riding Hood and other children's characters in between.[75] At other times the characters were conflated: in 1885 Mr Williamson's London Boutique in Sunderland was reported to be a "Temple of juvenile delectation and delight. In the well-lighted window is a representation of Begetter Christmas, with the printed intimation that 'Santa Claus is arranging within.'"[76]

Domestic Theatricals 1881

Even later the appearance of the store grotto, it was however not firmly established who should hand out gifts at parties. A author in the Illustrated London News of December 1888 suggested that a Sibyl should dispense gifts from a 'snow cavern',[77] just a picayune over a twelvemonth later she had changed her recommendation to a gypsy in a 'magic cave'.[78] Alternatively, the hostess could "have Father Christmas go far, towards the cease of the evening, with a sack of toys on his back. He must have a white head and a long white bristles, of course. Wig and beard can exist cheaply hired from a theatrical costumier, or may be improvised from tow in case of need. He should habiliment a greatcoat down to his heels, liberally sprinkled with flour as though he had but come from that land of water ice where Father Christmas is supposed to reside."[78]

Every bit undercover nocturnal visitor [edit]

The nocturnal visitor aspect of the American myth took much longer to become naturalised. From the 1840s it had been accustomed readily enough that presents were left for children by unseen easily overnight on Christmas Eve, just the receptacle was a thing of debate,[79] as was the nature of the visitor. Dutch tradition had St Nicholas leaving presents in shoes laid out on 5 December,[eighty] while in France shoes were filled by Père Noël.[79] The older shoe custom and the newer American stocking custom trickled only slowly into United kingdom, with writers and illustrators remaining uncertain for many years.[79] Although the stocking somewhen triumphed,[79] the shoe custom had still not been forgotten by 1901 when an illustration entitled Did y'all see Santa Claus, Mother? was accompanied by the verse "Her Christmas dreams / Have all come true; / Stocking o'erflows / and likewise shoe."[81]

Fairy Gifts by JA Fitzgerald showing nocturnal visitors in 1868, before the American Santa Claus tradition took concord.

Before Santa Claus and the stocking became ubiquitous, one English language tradition had been for fairies to visit on Christmas Eve to get out gifts in shoes prepare out in forepart of the fireplace.[82] [83]

Aspects of the American Santa Claus myth were sometimes adopted in isolation and practical to Father Christmas. In a brusk fantasy slice, the editor of the Cheltenham Chronicle in 1867 dreamt of being seized by the collar by Father Christmas, "rising up like a Geni of the Arabian Nights ... and moving speedily through the aether". Hovering over the roof of a house, Male parent Christmas cries 'Open up Sesame' to have the roof roll dorsum to disembalm the scene within.[84]

Information technology was not until the 1870s that the tradition of a nocturnal Santa Claus began to exist adopted past ordinary people.[nine] The verse form The Baby'southward Stocking, which was syndicated to local newspapers in 1871, took it for granted that readers would be familiar with the custom, and would sympathise the joke that the stocking might be missed as "Santa Claus wouldn't be looking for anything half so small."[85] On the other hand, when The Preston Guardian published its verse form Santa Claus and the Children in 1877 it felt the need to include a long preface explaining exactly who Santa Claus was.[86]

Folklorists and antiquarians were non, it seems, familiar with the new local customs and Ronald Hutton notes that in 1879 the newly formed Folk-Lore Society, ignorant of American practices, was nonetheless "excitedly trying to observe the source of the new conventionalities".[9]

In January 1879 the antiquarian Edwin Lees wrote to Notes and Queries seeking data about an observance he had been told nearly by 'a country person': "On Christmas Eve, when the inmates of a house in the country retire to bed, all those desirous of a present place a stocking outside the door of their sleeping room, with the expectation that some mythical being called Santiclaus will fill the stocking or place something inside it before the morning time. This is of course well known, and the master of the house does in reality place a Christmas souvenir secretly in each stocking; but the giggling girls in the morning, when bringing down their presents, affect to say that Santiclaus visited and filled the stockings in the night. From what region of the world or air this benevolent Santiclaus takes flying I have not been able to ascertain ..."[87] Lees received several responses, linking 'Santiclaus' with the continental traditions of St Nicholas and 'Petit Jesus' (Christkind),[88] only no-i mentioned Father Christmas and no-one was correctly able to place the American source.[48] [89]

Past the 1880s the American myth had get firmly established in the popular English imagination, the nocturnal visitor sometimes being known every bit Santa Claus and sometimes every bit Father Christmas (often consummate with a hooded robe).[9] An 1881 poem imagined a child awaiting a visit from Santa Claus and asking "Will he come like Father Christmas, / Robed in green and bristles all white? / Will he come amongst the darkness? / Will he come up at all this evening?"[ix] [90] The French writer Max O'Rell, who obviously thought the custom was established in the England of 1883, explained that Begetter Christmas "descend par la cheminée, pour remplir de bonbons et de joux les bas que les enfants ont suspendus au pied du lit." [comes down the chimney, to fill with sweets and games the stockings that the children have hung from the foot of the bed].[89] And in her poem Agnes: A Fairy Tale (1891), Lilian M Bennett treats the two names as interchangeable: "Old Santa Claus is exceedingly kind, / simply he won't come to Wide-awakes, you will find... / Male parent Christmas won't come if he can hear / You're awake. And so to bed my bairnies honey."[91] The commercial availability from 1895 of Tom Smith & Co's Santa Claus Surprise Stockings indicates how deeply the American myth had penetrated English society by the end of the century.[92]

Representations of the developing grapheme at this period were sometimes labelled 'Santa Claus' and sometimes 'Father Christmas', with a tendency for the latter still to allude to old-style associations with charity and with nutrient and drink, as in several of these Dial illustrations:

- Father Christmas in Punch, 1890s

-

The Awakening of Father Christmas 1891

-

"Where's your stocking?" 1895

-

Father Christmas Up-To-Engagement 1896

-

Father Christmas Non Up-To-Appointment 1897

20th century [edit]

Whatsoever residue distinctions betwixt Father Christmas and Santa Claus largely faded away in the early on years of the new century, and information technology was reported in 1915, "The majority of children to-24-hour interval ... do not know of any difference betwixt our one-time Begetter Christmas and the insufficiently new Santa Claus, as, by both wearing the same garb, they take effected a happy compromise."[93]

Information technology took many years for authors and illustrators to concord that Father Christmas'southward costume should be portrayed every bit red—although that was always the about mutual color—and he could sometimes be plant in a gown of brown, dark-green, bluish or white.[ane] [3] [70] Mass media blessing of the ruby-red costume came following a Coca-Cola advertising campaign that was launched in 1931.[1]

Father Christmas cartoon, Punch, December 1919

An English postcard of 1919 epitomises the OED's definition[21] of Father Christmas as "a personification of Christmas, now conventionally pictured as a benevolent old man with a long white bristles and cherry-red wearing apparel trimmed with white fur, who brings presents for children on the night before Christmas Day".

Father Christmas'south common grade for much of the 20th century was described by his entry in the Oxford English Lexicon. He is "the personification of Christmas as a benevolent former man with a flowing white beard, wearing a ruddy sleeved gown and hood trimmed with white fur, and carrying a sack of Christmas presents".[21] One of the OED's sources is a 1919 drawing in Punch, reproduced hither.[94] The caption reads:

- Uncle James (who after hours of making upward rather fancies himself as Father Christmas). "Well, my trivial man, and do you know who I am?"

- The Lilliputian Homo. "No, as a thing of fact I don't. But Male parent's downstairs; peradventure he may exist able to tell you."

In 1951 an editorial in The Times opined that while virtually adults may be nether the impression that [the English] Father Christmas is home-bred, and is "a skilful insular John Balderdash old gentleman", many children, "led away ... by the false romanticism of sledges and reindeer", post messages to Kingdom of norway addressed simply to Father Christmas or, "giving him a foreign veneer, Santa Claus".[95]

Differences between the English and US representations were discussed in The Illustrated London News of 1985. The classic analogy by the US artist Thomas Nast was held to be "the authorised version of how Santa Claus should wait—in America, that is." In Uk, people were said to stick to the older Male parent Christmas, with a long robe, large concealing beard, and boots similar to Wellingtons.[96]

Father Christmas Packing 1931, as imagined in a individual letter of the alphabet by JRR Tolkien, published in 1976

Father Christmas appeared in many 20th century English-linguistic communication works of fiction, including J. R. R. Tolkien's Father Christmas Letters, a series of private letters to his children written betwixt 1920 and 1942 and outset published in 1976.[97] Other 20th century publications include C. S. Lewis's The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), Raymond Briggs's Father Christmas (1973) and its sequel Father Christmas Goes on Holiday (1975). The character was also celebrated in popular songs, including "I Believe in Male parent Christmas" by Greg Lake (1974) and "Father Christmas" by The Kinks (1977).

In 1991, Raymond Briggs's two books were adjusted as an blithe brusque film, Father Christmas, starring Mel Smith as the voice of the championship grapheme.

21st century [edit]

Modern dictionaries consider the terms Father Christmas and Santa Claus to exist synonymous.[98] [99] The respective characters are now to all intents and purposes indistinguishable, although some people are still said to prefer the term 'Begetter Christmas' over 'Santa', virtually 150 years afterward Santa's arrival in England.[1] According to Brewer'due south Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (19th edn, 2012), Male parent Christmas is considered to be "[a] British rather than a US proper noun for Santa Claus, associating him specifically with Christmas. The name carries a somewhat socially superior cachet and is thus preferred past certain advertisers."[100]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Roud, Steve (2006). The English Twelvemonth. London: Penguin Books. pp. 385–387. ISBN978-0-140-51554-1.

- ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (1994). The Rising and Fall of Merry England . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN0-19-969104-5.

- ^ a b Duffy, Eamon (1992). The Stripping of the Altars. New Oasis and London: Yale Academy Press. pp. fourteen. ISBN0-300-06076-9.

- ^ a b Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 402. ISBN0-19-969104-5.

- ^ Duffy, Eamon (1992). The Stripping of the Altars. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 581–582. ISBN0-300-06076-9.

- ^ Nashe, Thomas (1600). Summertime's Concluding Will and Testament. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Whitlock, Keith (2000). The Renaissance in Europe: A Reader. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 181. ISBN0-300-082231.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hutton, Ronald (1996). The Stations of the Sunday . Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN0-nineteen-820570-8.

- ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (1994). The Rising and Fall of Merry England . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 212.

- ^ Macintyre, Jean (1992). Costumes and Scripts in Elizabethan Theatres . University of Alberta Printing. p. 177.

- ^ Austin, Charlotte (2006). The Celebration of Christmastide in England from the Ceremonious Wars to its Victorian Transformation. Leeds: University of Leeds (BA dissertation). p. eleven. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved xiv January 2016.

- ^ "Christmas, His Masque – Ben Jonson". Hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Nabbes, Thomas (1887). Bullen, AH (ed.). Sometime English language Plays: The Works of Thomas Nabbes, volume the second. London: Wyman & Sons. pp. 228–229.

- ^ a b c Durston, Chris (Dec 1985). "The Puritan War on Christmas". History Today. 35 (12). Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved fourteen January 2016.

- ^ An Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals. Official parliamentary record. 8 June 1647. Archived from the original on 27 Jan 2016. Retrieved 16 Jan 2016. Quoted in Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660, ed. CH Firth and RS Rait (London, 1911), p 954.

- ^ Pimlott, JAR (1960). "Christmas nether the Puritans". History Today. ten (12). Archived from the original on 28 Jan 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Austin, Charlotte (2006). The Commemoration of Christmastide in England from the Civil Wars to its Victorian Transformation. Leeds: University of Leeds (BA dissertation). p. 7. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2016. Retrieved xiv Jan 2016.

- ^ Anon (1645). The Arraignment Conviction and Imprisonment of Christmas on Due south. Thomas Day Last. London, "at the signe of the Pack of Cards in Mustard-Alley, in Brawn Street": Simon Minc'd Pye, for Cissely Plum-Porridge. Archived from the original on thirty December 2015. Retrieved fifteen Jan 2016. Reprinted in Ashton, John, A righte Merrie Christmasse!!! The Story of Christ-tide Archived viii Oct 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Leadenhall Press Ltd, London, 1894, Chapter IV.

- ^ Taylor, John (published anonymously) (1652). The Vindication of Christmas or, His Twelve Yeares' Observations upon the Times. London: G Horton. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved xiv Jan 2016. (Printed date 1653)

- ^ a b c "Begetter Christmas". Oxford English Lexicon (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2020. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Giving Christmas his Due". 23 Dec 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ King, Josiah (1658). The Examination and Tryall of Old Father Christmas. London: Thomas Johnson. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ a b Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 62. ISBN0-19-969104-5.

- ^ King, Josiah (1678). The Exam and Tryal of Sometime Father Christmas, together with his immigration by the Jury, at the Assizes held at the town of Deviation, in the county of Discontent. London: H Brome, T Basset and J Wright. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2012. The online transcript is from a subsequently reprinting of 1686.

- ^ Old Christmass Returnd, / Or, Hospitality REVIVED. Printed for P. Brooksby. 1672–1696. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 31 Dec 2016. Transcription also at Hymns and Carols of Christmas Archived 23 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (1994). The Rising and Autumn of Merry England . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 242–243.

- ^ Austin, Charlotte (2006). The Commemoration of Christmastide in England from the Civil Wars to its Victorian Transformation. Leeds: University of Leeds (BA dissertation). p. 34. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Merryman, Dick (1734). Round about our Coal Fire, or, Christmas Entertainments. London: Roberts, J. quaternary edn reprint of 1796 on Commons

- ^ Pimlott, JAR (1978). An Englishman's Christmas: A Social History. Hassocks, Suffolk: The Harvester Press. p. 63. ISBN0-391-00900-one.

- ^ Garrick, David (1774). A new dramatic amusement, chosen a Christmas Tale: In five parts. The corner of the Adelphi, in the Strand [London]: T Becket. Archived from the original on xvi February 2016. Retrieved nine February 2016.

- ^ a b c Millington, Peter (2002). "Who is the Guy on the Left?". Traditional Drama Forum (6). Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2015. Spider web page dated Jan 2003

- ^ Roud, Steve (2006). The English Year. London: Penguin Books. p. 393. ISBN978-0-140-51554-1.

- ^ Millington, Peter (2002). The Origins and Development of English Folk Plays (phd). University of Sheffield: Unpublished. Archived from the original on xxx January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Millington, Peter (2002). "Textual Analysis of English Quack Dr. Plays: Some New Discoveries" (PDF). Folk Drama Studies Today. International Traditional Drama Conference. p. 106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b Millington, Peter (December 2006). "Male parent Christmas in English Folk Plays". Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Millington, Peter (April 2003). "The Truro Cordwainers' Play: A 'New' Eighteenth-Century Christmas Play" (PDF). Folklore. 114 (i): 53–73. doi:10.1080/0015587032000059870. JSTOR 30035067. S2CID 160553381. The article is also available at eprints.nottingham.ac.u.k./3297/i/Truro-Cordwainers-Play.pdf.

- ^ Millington, Peter (ed.). "Truro [Formerly Mylor]: "A Play for Christmas", 1780s". Archived from the original on iii March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Scott, Walter (1808). Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field.

- ^ Roud, Steve (2006). The English Year. London: Penguin Books. pp. 372, 382. ISBN978-0-140-51554-ane.

- ^ Daseger (24 December 2014). "Daily Archives: Dec 24, 2014 - Mummers Mumming". streetsofsalem. Archived from the original on ane February 2016. Retrieved xx January 2016.

- ^ Hervey, Thomas Kibble (1836). The Book of Christmas: descriptive of the customs, ceremonies, traditions, superstitions, fun, feeling, and festivities of the Christmas Flavour. pp. 42, 285. . The online version listed is the 1888 American printing. Higher-resolution copies of the illustrations tin also be found online Archived 14 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hervey, Thomas Kibble (1836). The Volume of Christmas: descriptive of the customs, ceremonies, traditions, superstitions, fun, feeling, and festivities of the Christmas Season. pp. 114–118. .

- ^ Hervey, Thomas Kibble (1836). The Volume of Christmas: descriptive of the customs, ceremonies, traditions, superstitions, fun, feeling, and festivities of the Christmas Season. pp. 133.

- ^ Bowler, Gerry (2000). The Globe Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd. pp. 44. ISBN0-7710-1531-3.

- ^ Dickens, Charles (19 December 1843). A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost-Story of Christmas. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 79.

- ^ Hervey, Thomas Kibble (1836). The Book of Christmas: descriptive of the customs, ceremonies, traditions, superstitions, fun, feeling, and festivities of the Christmas Season. pp. 65.

- ^ a b c d "Gifts And Stockings - The Foreign Case Of Begetter Christmas". The Times. 22 Dec 1956. p. 7. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Pimlott, JAR (1978). An Englishman'due south Christmas: A Social History. Hassocks, Suffolk: The Harvester Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN0-391-00900-1.

- ^ Sandys, William (1852). Christmastide, its History, Festivities and Carols. London: John Russell Smith. pp. 152.

- ^ Millington, Peter (2002). "Textual Analysis of English Quack Doctor Plays: Some New Discoveries" (PDF). Folk Drama Studies Today. International Traditional Drama Conference. p. 107. Archived from the original (PDF) on iii February 2013. Retrieved 19 Jan 2016.

- ^ Bede, Cuthbert (vi April 1861). "Mod Mumming". Notes & Queries. 11 (2d series): 271–272. ('Cuthbert Bede' was a pseudonym used by the novelist Edward Bradley).

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1864). The Book of Days. A Miscellany of Pop Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar. Book II. London: Due west & R Chambers. pp. 740. The online version is the 1888 reprint.

- ^ Walcott, Mackenzie EC (1862). "Hampshire Mummers". Notes & Queries. 1 (Third series).

- ^ Pimlott, JAR (1978). An Englishman's Christmas: A Social History. Hassocks, Suffolk: The Harvester Press. p. 136. ISBN0-391-00900-1.

- ^ Roud, Steve (2006). The English Year. London: Penguin Books. p. 396. ISBN978-0-140-51554-1.

- ^ Pimlott, JAR (1978). An Englishman's Christmas: A Social History. Hassocks, Suffolk: The Harvester Press. p. 85. ISBN0-391-00900-one.

- ^ Fox, Berkley (2008). Brett, RL (ed.). Barclay Fox's Journal 1832 - 1854. Cornwall Editions Limited. p. 297. ISBN978-1904880318. Some of the entries were first published nether the title Barclay Fob'due south Journal, edited past RL Brett, Bell and Hyman, London 1979.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (fourteen December 2019). "Outset letter to Begetter Christmas discovered from girl requesting paints in 1895". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 Jan 2022.

- ^ The Children's friend. Number III. : A New-Year's present, to the trivial ones from five to twelve. Part III. New York: Gilley, William B. 1821. Archived from the original on half-dozen February 2016. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016.

- ^ Howitt, Mary Botham (ane January 1848). "New year's day's Eve in Different Nations". Howitt's Journal of Literature and Popular Progress. 3 (53): 1–3.

- ^ "Liverpool Mercury". Notices for Emigrants for 1851. Michell's American Passenger Office. For New York. "Eagle Line". Liverpool. 25 April 1851. p. 4. Retrieved 31 Jan 2016.

- ^ "New year". John o' Groat Journal. Caithness, Scotland. ix January 1852. p. 3. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Works of Love". Armagh Guardian. Armagh, Northern Republic of ireland. 25 November 1853. p. 7. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016.

- ^ "The Little Stockings". The Belfast News-Letter of the alphabet. Belfast. 2 February 1858. Retrieved fourteen Feb 2016.

- ^ Uneda (24 December 1853). "Pennsylvanian Folk Lore: Christmas". Notes & Queries. 8: 615. A farther online re-create can be found here Archived vii March 2016 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ a b Armstrong, Neil R (2004). The Intimacy of Christmas: Festive Celebration in England c. 1750-1914 (PDF). University of York (unpublished). pp. 58–59. Archived (PDF) from the original on four February 2016. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016.

- ^ Warner, Susan (1854). Carl Krinkin; or, The Christmas Stocking. London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co.

- ^ Pimlott, JAR (1978). An Englishman'due south Christmas: A Social History. Hassocks, Suffolk: The Harvester Press. p. 117. ISBN0-391-00900-one.

- ^ a b "Yule Tide Festivities at Luton". Luton Times and Advertiser. Luton, Bedfordshire, England. two January 1855. p. 5. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Christmas Readings". Hereford Periodical. Hereford. 27 December 1854. p. 4.

- ^ "The Cave of Mystery". Illustrated London News: 607. 22 December 1866. The epitome was republished in the United States a year after in Godey'south Ladies Book, December 1867, under the championship 'Sometime Father Christmas'.

- ^ a b c Connelly, Mark (2012). Christmas: A History. London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. pp. 189, 192. ISBN978-1780763613.

- ^ Armstrong, Neil R (2004). The Intimacy of Christmas: Festive Celebration in England c. 1750-1914 (PDF). Academy of York (unpublished). p. 261. Archived (PDF) from the original on four February 2016. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016.

- ^ "The Times". Olympia. - Boxing Day. London. 26 December 1888. p. 1. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Christmas Preparations in Sunderland". Sunderland Daily Echo and Aircraft Gazette. Tyne and Wear. 19 December 1885. p. 3.

- ^ Fenwick-Miller, Florence (22 Dec 1888). "The Ladies' Cavalcade". Illustrated London News: 758.

- ^ a b Fenwick-Miller, Florence (iv Jan 1890). "The Ladies' Column". The Illustrated London News (2646): 24.

- ^ a b c d Henisch, Bridget Ann (1984). Cakes and Characters: An English Christmas Tradition. London: Prospect Books. pp. 183–184. ISBN0-907325-21-one.

- ^ "Sinterklaas". NL Netherlands. iii May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Did yous see Santa Claus, Mother?". Illustrated London News: 1001. 28 December 1901.

- ^ Locker, Arthur (28 December 1878). "Christmas Fairy Gifts". The Graphic. London.

- ^ MJ (19 December 1868). "Fairy Gifts". Illustrated London News. London. p. 607. Retrieved half-dozen February 2016.

- ^ "Our Christmas Corner. The Editor's Dream". Cheltenham Relate. Cheltenham. 24 Dec 1867. p. 8.

- ^ "The Baby's Stocking". Essex Halfpenny Newsman. Chelmsford. 8 April 1871. p. ane. The poem was also published in Leicester Relate and the Leicestershire Mercury, Leicester, 11 March 1871, page two.

- ^ "Christmas Rhymes: Santa Claus and the Children". The Preston Guardian. Preston. 22 Dec 1877. p. 3. Retrieved xvi February 2016.

- ^ Lees, Edwin (25 January 1879). "Gifts Placed in the Stocking at Christmas". Notes & Queries. 11 (Fifth series): 66.

- ^ Lees, Edwin (five July 1879). "Gifts Placed in the Stocking at Christmas". Notes & Queries. 12 (Fifth series): xi–12.

- ^ a b Pimlott, JAR (1978). An Englishman'due south Christmas: A Social History. Hassocks, Suffolk: The Harvester Press. p. 114. ISBN0-391-00900-1.

- ^ "The Children's Column". The Leeds Mercury Weekly Supplement. Leeds. 24 December 1881. p. 7.

- ^ Bennett, Lilian Yard (twenty February 1891). "Agnes: A Fairy Tale (part I)". Manchester Times. Manchester.

- ^ Armstrong, Neil R (2004). The Intimacy of Christmas: Festive Celebration in England c. 1750-1914 (PDF). University of York (unpublished). p. 263. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 Feb 2016. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016.

- ^ "Santa Claus". Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser. Sevenoaks. 31 December 1915. p. 3. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Dial". 157. 24 Dec 1919: 538.

- ^ "Simple Faith". The Times. London. 21 December 1951. p. seven. Retrieved vii February 2016.

- ^ Robertshaw, Ursula (2 December 1985). "The Christmas Gift Bringer". Illustrated London News (1985 Christmas Number): np.

- ^ Tolkien, JRR (1976). The Father Christmas Messages. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. ISBN0-04-823130-iv.

- ^ "Father Christmas". Collins English Dictionary. Collins. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved viii February 2016.

- ^ "Male parent Christmas". Chambers 21st Century Dictionary. Chambers. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Dent, Susie (forrard) (2012). Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (19th edn). London: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd. p. 483. ISBN978-0550107640.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Male parent Christmas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Male parent Christmas at Wikimedia Commons

Merry Christmas Baby You Sure Have Treated Me Well

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Father_Christmas

0 Response to "Merry Christmas Baby You Sure Have Treated Me Well"

Post a Comment